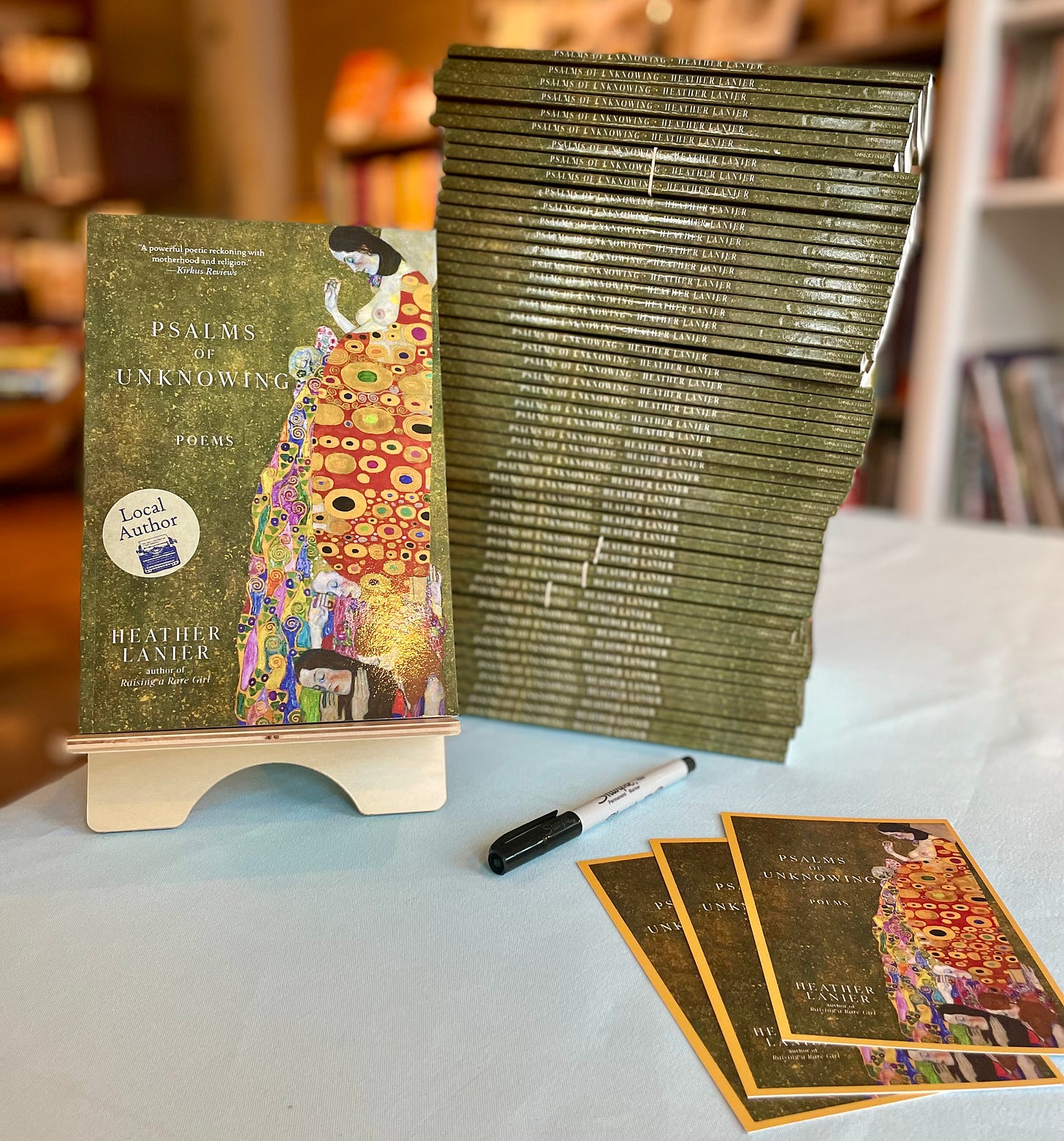

Helllooooo, readers! We have some new folks here, courtesy of an essay I wrote for Jane Friedman’s website. In today’s post, I’m resharing that essay, about the stumbling blocks I met while putting together my latest book, Psalms of Unknowing. Kirkus Reviews called it a “powerful poetic reckoning with motherhood and religion,” but at one point, it could have just been called “a scrambled mess on a living room carpet.”

That’s how all art is, though! We usually just see the finished product, not the process behind it. But I find the process super interesting. If you do too, this post is for you. And if you’ve ever found yourself running from what you’ve really wanted to say, maybe because you worried the world wouldn’t value it, this post is also for you. Read on…!

The problem was Jesus. He kept appearing in my poems. And not even in the way typical fans of Jesus would like. He was peculiar: silently doodling in sand, or teetering with endearing doubt, or kind-of sexy in chiseled statue-form, suspended on a human-sized cross. Christians would not dig some of this. Nor (I assumed) would the literary poetry world, whose faith tolerance is limited.

As I tried to assemble a decade of my published poems into a book-length manuscript, I found other issues: Eve, remembering how much she loved going naked. Mary, of all people, pregnant and worrying about carting God-in-human-form above her pelvis. And sweet Lord, I even sometimes used the word God—that abyss-deep noun we pretend we all agree on the definition of.

This was why, when I first spread the dozens of poems across my office floor and tried to assemble them into a book, I thought: I need to bury the Jesus poems. And the overtly religious poems. I need to hide them behind the poems about misogyny and motherhood and pandemic politics and grief.

It was a classic move: Believe what you have to say isn’t worthwhile. Hide it. Try to turn yourself into another kind of writer.

I’m a professor in a graduate writing program at a university in New Jersey. By year’s end, my students must write a 30,000-word manuscript. For many, it’s the longest project they’ve ever attempted. Almost none of them are writing about religion, and yet many still fall into this same trap as I did—thinking they should become a different kind of writer. They’re poets, but they suspect nobody reads poetry, so they try a novel instead. That’s what real writers do, right? they think. Or they’ve got an important personal story to tell, but they fear the earthquake their words could cause in the tectonic plates of their lives, so they decide to write … a fantasy sci-fi novel instead! Or they want to write a fantasy sci-fi novel, but someone in their family dismisses the entire genre, so they embark on some heady nonfiction project about narrative theory.

There are as many variations on this theme as there are writers. About a month into the fall semester, each student usually returns to their callings, however scary. The poet realizes she has no interest in plot. The sci-fi-attempter learns that, even on an invented planet, he can’t escape himself. The person longing to write sci-fi can’t say no to the strange world in her mind.

At the end of the year, I read reflection after reflection about writers trying to run away from their true subjects. About how much time they wasted doing this. About how scared they were of what they had to say. And about how, eventually, they came home to themselves.

You’d think, as a professor of writing, I would have caught myself immediately. You’d think I would have been able to identify the trapdoor before stepping into it. Instead, I thought I was being savvy. Bury the poems about faith!

Alas, I suspect every writer is prone, at one time or another, to the new shapes this trapdoor takes, the surprising ways it can appear in the house of our psyches.

And so, I tried to bury the Jesus poems. This wasn’t particularly hard. Motherhood is another heavy theme of mine. (Ah yes, another subject the literary world has a history of heralding without caveats or condescension—and yes, if we agreed on a sarcasm font, I’d be using it right now.) So, pregnancy kicked off the collection—so much pregnancy poetry, in fact, that the manuscript felt like it would keel over from the weight of a disproportionately ginormous belly.

Then came the babies, along with a second section on motherhood. Section three is where I stuck Christ and Mary, et. al. But then I tied it all up with a globally impactful fourth section on political issues—you know, important public stuff. “Masculine” stuff.

Do you see the other trapdoor here? It’s a particularly gendered one, architected from a woman having to contend with misogynistic readings of her work as drivel because it finds revelation in the domestic, in the private. (Memory: a male chair of a hiring committee tells me in an interview that all the good nonfiction is not memoir but researched writing, about things like war. I was writing a memoir. I did not get the job.) By ending the collection on this “public” material, I was attempting another kind of running from the self.

The problem, of course, is that the book didn’t work. It turns out that it never works to run from ourselves—not in regular life, and not in art-making, either. (I don’t know whether to be relieved about this or dismayed.) You know how I knew I was in trouble? The manuscript couldn’t find its title. This meant I didn’t know what was binding the thing together. Which meant a reader wouldn’t either.

I like to think all our good ideas come from our inner wisdom—that faithful compass inside each of us. Weirdly, the way I got out of my rut came, of all places, from Facebook. It came when I saw a call from an editor seeking literary manuscripts specifically about spirituality. Poetry, novels, essay collections—Anne McGrath at Monkfish Publishing was open to any genre. And any religion. She just wanted work that was both literary and spiritually curious.

I finally asked a question every artist probably needs to consider at some point in their lives: What if the thing I’m trying to bury is the thing that needs to come forward?

I spread the poems out across the office floor again. I thought about what a book would look like if the collection began with religious wrestling. What if my shaky faith and ongoing doubt and incessant yearning for the Divine appeared as a thread, stitched throughout, rather than a hard-to-digest middle chunk?

Something weird happened. The collection started to cohere. Poems about the wildness of being pregnant got bigger beside my speculation about Mary’s pregnancy. My grief over a family member’s murder was more powerful next to my floundering attempts at prayer. My rage about the absence of women in a kid’s toy became more interesting when placed near a poem about Jesus stopping an angry mob from stoning a woman. I still created four sections, and the poems are unmistakably from a feminist mother’s perspective. But the whole collection begins—and ends—with spiritual seeking.

We sometimes think of poetry as dismissing of audience, as privileging the writer’s intentions over the reader’s presence. It was the presence of an actual audience, this time in the form of an independent publisher, that helped me conceive of my collection. I arranged and rearranged it. I called it Psalms of Unknowing. I sent it to Monkfish. One month later, they accepted it.

Maybe it will always be our plight, as writers, to try to turn ourselves into other kinds of writers. The versions of this trapdoor are numerous, as newly constructed as any piece of art we try to make. But our ways of getting out of them are equally varied: an intuitive voice, a smart response from a friend, even a post on Facebook.

For more thoughts on art-making and writing through uncertainty, check out my conversation with Meredith Hite Estevez at

.

This is great and rings so true. I resisted/hid from the fact that I was writing poems about motherhood because I worried that subject would be considered sentimental and not serious/literary (barf), but then when I finally put them all in a chapbook, it worked and made sense. And then I wrote a novel that is pretty weird, and I tried to un-weird it, and it just didn’t work, so I let it be what it is--and it was accepted for publication! Why do we resist ourselves like this??