Welcome to The Slow Take, my very occasional newsletter about the strangeness and beauty of being human. I’m Heather Lanier, author of the memoir, Raising a Rare Girl, and the poetry collection, Psalms of Unknowing. I’m glad you’re here.

It’s summer, which means we’re all probably more aware of our bodies than usual. Thighs rub together. Shorts ride up. Sweat pours. Swimsuits reveal a square-footage of skin unthinkable to our winter selves. We publicly slather sunscreen on jiggly bits we otherwise rarely touch—or even think about. Our cellulite is on full display for any member of the neighborhood pool, including our kids’ teachers. Hello, Mrs. Smith! How’s your summer?

I mean: Like no other season, the body is front and center in the summer.

I showed up at our town’s four-mile race wearing nothing on top but a sports bra, because thank God women are doing this now. I felt fine about it because ninety-five degrees, until I ran into the priest of my local Episcopal church and realized I was wearing, well, nothing on top but a sports bra. Hello, Father! (Also, if you read this, Hello, Father. It was fine. Bodies are good. Go us, for running 4 miles!)

My children’s bodies are also front and center in the summer. I have at least one preteen who’s eager to bare her midriff, and I’m letting her (because a creepy Christian school in the eighties used to shame us kids for bearing even a millimeter of our bellies. Screw them. Bodies/bellies are good.)

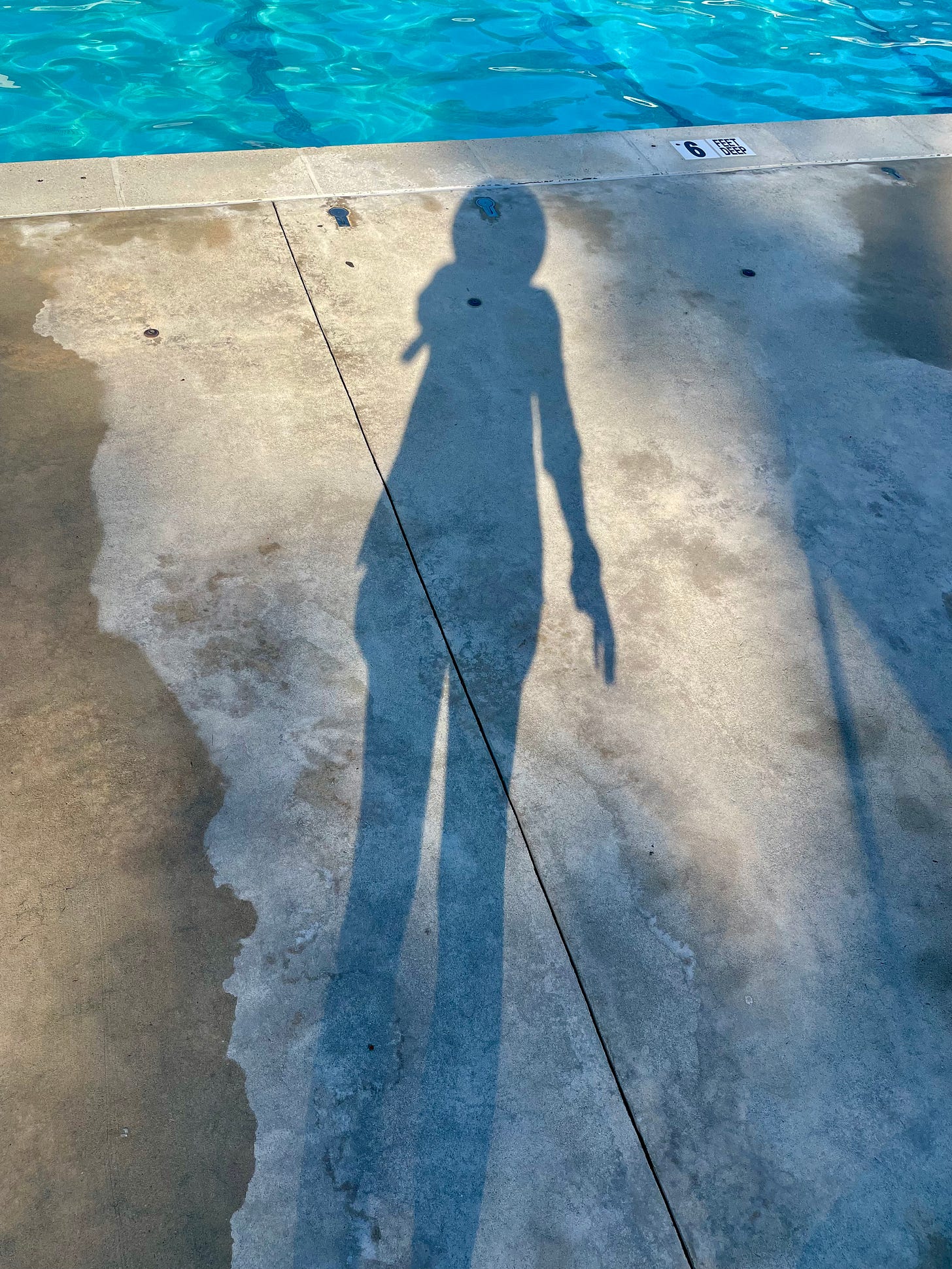

And I have another kid whose body attracts infinitely more stares in the summer than at any other time of year.

Dear reader, it’s surprisingly intense, the staring. It kind-of knocks me off my game. The people who stare are usually between the ages of seven and fifteen. The staring almost always occurs at the local pool, where my daughter is wearing a swimsuit and a flotation device around her fifty-pound, thirteen-year-old frame. (For those that don’t know, my oldest has a rare chromosomal syndrome. I wrote this book about it.)

My response is futile and knee-jerk: I stare back. I stare and stare until maybe they’ll stop staring. But they don’t. I buckle my eyebrows together, furrow, frown, think maybe this stern face will shake them out of their open-mouthed trance. It does not, because they are not looking at me.

I’m baffled by the staring, because the target of their staring is a thirteen-year-old human who is totally normal to me, and whom I carried in my center for nine months, and whose cells still float around inside me. I mean, this is my love they are staring at.

But her body must be super anomalous to them, because the staring has only increased as she’s gotten older.

Normal is just a setting on the dryer, people like to say. But “Normal” is tyrannical. It has taught us to be very concerned by bodies that fall outside of it. I mean to say: The person who believes normal is just a setting on a dryer is deceiving themselves about the power that many folks, including possibly them, attribute to Normal. (Sometimes it feels like Normal has been given absolute immunity, if you know what I mean.)

What works best is what I keep forgetting to do: I say to the starer, almost amiably but also aggressively: “Hello!” This single word usually shakes the person out of their staring. They say hi back. If they don’t, I add in the same aggressively friendly tone: “I’m Heather, what’s your name!?”

This usually serves as an antidote to their gaze, maybe because it’s a version of, You are a person, I am a person. Please treat people like people.

I’m watching Crip Camp for the first time. (I know, I know: I’m way overdue.) If you haven’t seen it, it’s about a revolutionary Catskills summer camp for disabled teens during the seventies. My favorite moment so far happens about twelve minutes in, when Jim LeBrecht, who was born with spina bifida, described his nervousness on night one of camp. Some of the video footage shows him reflecting today, with curly hair, a white goatee, and salmon button-up. Some of the video footage shows him back then, as a frizzy-haired teenager of the seventies, pushing his wheelchair down a cabin ramp.

“I had just had surgery,” he said. “Up to that point, I was wearing diapers. Because I had no control over my bladder…. I guess you could imagine what it was like, being fifteen, and trying to hide the fact that you had to wear diapers? And there was that constant pressure… of being found out…. I had gotten this urinary tract diversion, so now I had this bag. And it wasn’t going too well. I was having a hard time kind-of keeping it on, and it was leaking and such.”

There’s a photo of him with his high school class. He’s front and center in his wheelchair. Behind him is a row of kids kneeling, another row of kids standing.

Then he added: “But at camp, everybody had something going on with their bodies. It just wasn’t a big deal.”

I don’t know why this part makes me tear up. Makes my heart sing. Makes me long for a certain kind of heaven, one where all bodies are openly as they are, and many bodies have things going on with them, and it just isn’t a big deal. No staring. No shame. Just bodies being themselves. And people living imperfectly and maybe even joyfully inside them.

(Sidenote: This heaven might be the opposite of what evangelicals describe, when they say they’ll get “celestial bodies,” which I think means somehow “perfect” and having nothing “going on”…. and being, consequently, not very interesting.)

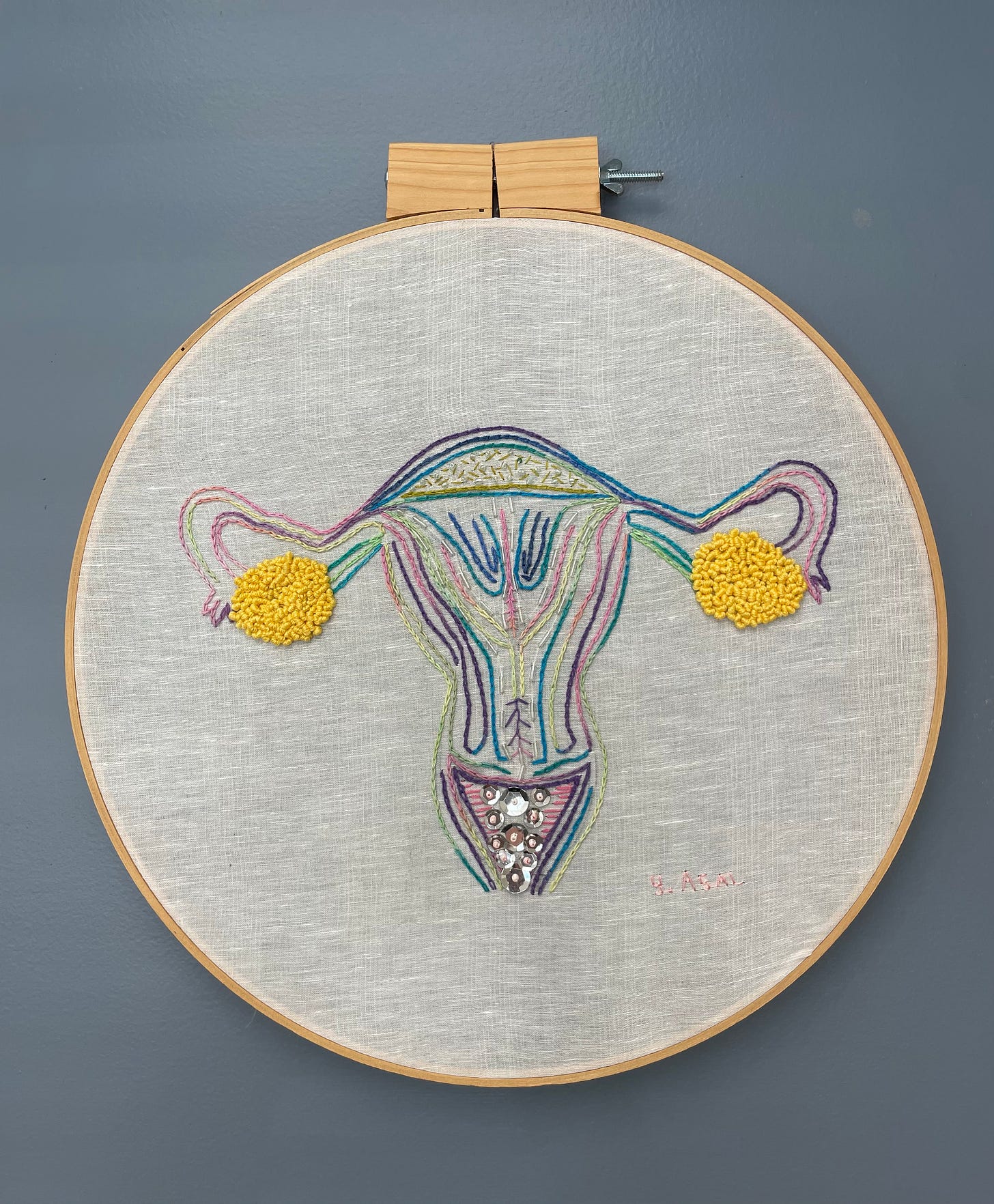

I guess I teared up at the quote because many of us actually do have something going on with our bodies. For real. And us non-disabled folks have created a world where we all are supposed to pretend otherwise. No IBS. No migraines. No ileostomy bags. No need to fart. No panic attacks. No pelvic floor trouble. No PMS.

Additional sidenote: This spring, my youngest daughter came home from school after the “puberty talk.” The nurse, a particularly uncompassionate woman who seems irritated when sick kids show up at her office, told the class that menstrual cramps should never lead them to miss anything. That they should always be able to push through cramps. This means it’s possible that she just created a room of two different kinds of future women. One: those who will have debilitating cramps but feel like weaklings for succumbing to them. Two: those who will have mild cramps, or none at all, and who think their cramp-suffering sisters just need to suck it up. In other words: people without compassion for themselves, and people without compassion for each other.

I spent the early summer with something “going on with my body.” I spent last spring with a different thing “going on with my body.” And I spent the spring before that with another thing “going on with my body.” I’ll spare you the details. One of them was truly frightening because if you googled the symptoms—which I did—you were on the verge of spontaneously combusting. Or something like that. Another was disabling enough that I could barely leave the house. The most recent thing was only minorly inconvenient, but it still reminded me: the body is sometimes noisy. The body has things to say. The body is not under my control.

Also, the body is not the problem because of this. Perhaps when we expect bodies—our own or other people’s—to be otherwise, we become the problem.

My thirteen-year-old, fifty-pound, willowy daughter really likes to work out. So we do a lot of exercise videos. These videos feature ripped, thin women telling us things like, “The only thing between you and your goals is you!” Really, Ms. Cardio-Karen? I thought social support for caregivers might also be in my way? Or the Internet stuffing my brain with the most perfect algorithmic sales pitches when I’m just trying to write a work email? Or, how about the collective anxiety of a torn nation expressed through my particular nervous system at 3 a.m.?

But whatever. My kid loves planks and burpees. So we don our matching workout pants. We wear only bras on top (see above). We hit play. Today, I was chest pressing dumbbells when I heard her say this:

“A strong body is the physical representation of a strong mind. When you see someone with a strong healthy body, it’s earned…. It’s something to aspire to.”

I hit pause. Wrote the quote down. Shouted to my husband about it. He was in the kitchen. “The problem with this is that the inverse then becomes true: A weak body becomes the physical representation of a weak mind. Which is bullshit.”

Of course, that’s not the only problem with the quote. It’s just the only one I could articulate mid-chest-press. The other problem is: How can we tell which body is “strong”? Which body is so-called “healthy”? Just by looking? We absolutely cannot tell.

What is it about bootstraps American individualism that it wants to get under the sheets with ableism?

Crip Camp opens with Jimmy LeBrecht as a young boy, getting around his childhood home with his arms. His legs slide behind him. He pulls himself up onto a chair. He pours himself a cup of water from the tub—more accessible than a sink. Is he strong and healthy? I don’t know. He sure seems it.

But being “strong and healthy” as a virtue isn’t the point. Our bodies will, at some point, fail us. Our “strong minds” will not be the antidotes to such a truth. In fact, nobody’s gonna bring their body into the Great Beyond. They are temporary homes, and they are beautiful and wrinkly and glimmering and ashy and floppy and taut and skinny and fat. They don’t all have eyes, or ears, or legs, or even bladders. But they have hearts, all of them.

May your hearts sing in your bodies this summer, sweaty-thighed and skin-bearing and all.

Happy pub day to Jessica Slice and Caroline Cupp for their book, Datable: Swiping Right, Hooking Up, and Settling Down While Chronically Ill and Disabled! Y’all, we have to order this book! First, how amazing is that subtitle? Second, Jessica Slice and Caroline Cusp are legit. When they were researching for their illustrated children’s book, This is How We Play (out in September), they interviewed disabled kids, including my daughter—and they compensated them. They’re committed to disability advocacy. Congrats, Jessica and Caroline! Here’s a bit about the book:

“Datable is the first book on disabled dating and relationships; it's a dating guide made especially for disabled and chronically ill people, that also calls in nondisabled readers. Jessica and Caroline take on everything from rom-com representation and dating apps to sex and breakups with a strong narrative underpinning and down-to-earth advice. The book is as much a practical tool as it is an empowering guide.”

Yes to all of this. I wish it was easier to explain to nondisabled people that albleism hurts them too. Ableism is why they work too much even when they are exhausted. Ableism is why they hide things like pelvic floor issues and other things instead of sharing them and getting support and connection. Ableism is way they don't take sick days.

As a disabled woman who has been stared at my whole life, I think proper disability representation (and accessibility!) would make things so much better. Imagine if kids grew up seeing different bodies regularly in books and on TV and in movies. Kids stare at me because I am probably the first person with a limb difference they have ever seen. And I get that! But it doesn't get any less exhausting.

Thanks for your advocacy and your voice.

Amen amen! Bodies are good! Why is it so hard to work against the deeply ingrained messaging that any deviation - from the very narrow representation of “ideal” - is undesirable?