When I was in graduate school, I spent a year trying to get a 14-page lyric essay right. It was about the Buddhist concept of the hungry ghost. It was about craving and wanting, and the difference between desire and love. I kept thinking it was done, and kept receiving feedback that it wasn’t.

I bemoaned my slow pace to my professor, Lee Martin. I thought slow speed meant poor writer. “Will I get faster?” I asked Lee, because at this point, a year per essay would mean a pretty low output for a writer. He shrugged and said something like, “Maybe your standards are just getting higher. Maybe that’s just how long it takes.”

I did not love this answer.

But once I finished that essay, it was accepted for publication quickly. Then it landed on The Best American Essays’ notables list.

Twenty years later, I’m used to an essay taking a year. Not all essays. But certain ones. The ones that need an intellectual Olympics of research and an excavating of the soul.

My most recent “it took a year” essay was “The Heart Wing,” which is about how modern science perceives our hearts (and by extension us) as machines, and how our hearts (and by extension us) are mystically so much more than machines.

The essay starts off in the heart exhibit at the Franklin Institute. It meanders off into topics like the hundreds-year-old imperishable heart of a saint, the way grief can change the literal shape of our heart, and the Tibetan phenomenon of tuchdum—which is when the heart stops beating but oxygen still circulates in the body—for days or sometimes weeks!

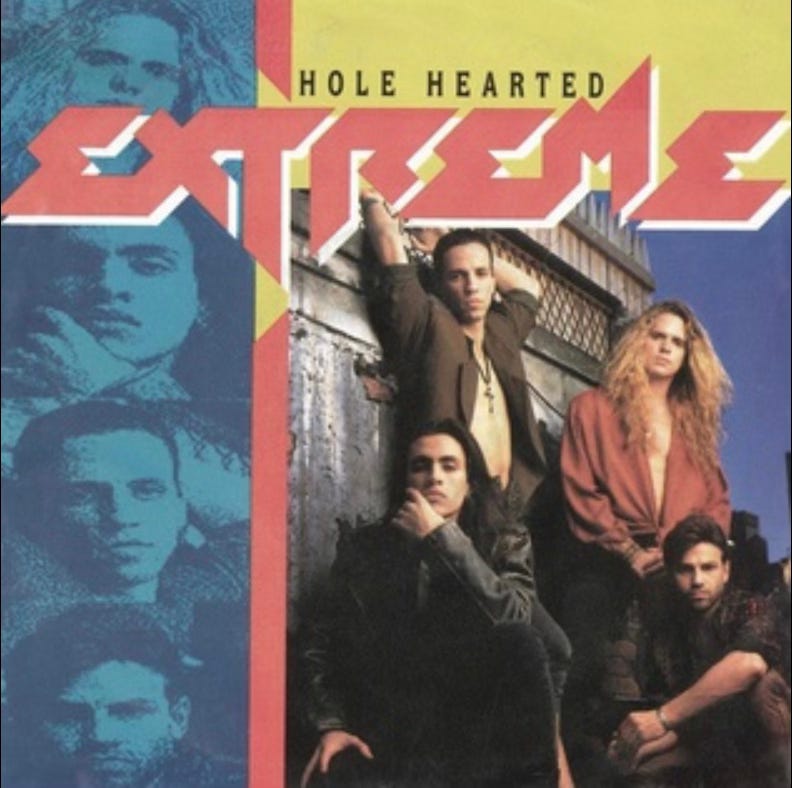

In that essay, I also mention the early 90s song by Extreme, “Hole-Hearted.” Remember that one? There’s a hole in my heart… that can only be filled by yoooo. I reference the song because I mention that my daughter once had a literal hole in her heart, but the hole closed.

Flash forward to last spring. I had to take my daughter, Fiona, to cardiology for a check-up. It was supposed to be no big deal, a “nothing to see here” appointment. Instead, the echocardiogram found that the hole never actually closed; it had gotten bigger.

On the way home, as south Jersey vape and pizza shops passed by, what played on the radio? That freaking Extreme song. “Hole-Hearted.” I hadn’t heard it since I was writing “The Heart Wing.” I hadn’t heard it since writing publicly that my daughter once had a hole in her heart, but that the hole closed.

One of the things about being a writer is that we’re always asking, What does it mean?

What does it mean that there’s a hole in my heart, that can only be filled by yooo plays on the radio on the day that I learn my daughter needs her heart-hole filled?

Does it mean doom? Does it mean comfort? I wondered these things. Is God/The Universe trying to say something?

A few months later, when we walked into the Children’s Hospital of Pennsylvania, and we wandered among the bad lighting and beige beeping machines, I asked: What does it mean? This place? This chaotic maze? This labyrinth of receptionists who’d gone missing, and nurses who were trying to cover for receptionists (but were annoyed about it), and doctors who were not yet available, and daughters—or my daughter—who was crying because EKG’s were Very Upsetting to her. Like, we were clearly torturing her with noninvasive sticker-things attached by wires to a machine that would tell doctors something about the electrical factors of her heart but that, by day’s end, no one would actually explain to us. Also, there was a consent form on an iPad that said things like, “Your beloved could die from what we’re about to do.”

What did it mean? It all just felt like chaos.

Hospitals are not just physically risky places—they’re emotionally risky, too. The nephrologist might offer a hearty congratulations at the birth of your kid with a rare syndrome. But the nurse might complain that your daughter’s urethra is too small for all her catheters. Or the doctor might treat you like a series of problems rather than a person, but the nurse touches your forearm and asks about your dinner plans and suddenly you’re human again. The receptionist might delight you or kind-of detest you. The other patients might stare, or might smile. Hospitals are a grab-bag of cultural weirdness, mixed with the condescension of medical arrogance and the potential deliverance of medical grace.

But back to essays that take a year. Or maybe not back to those. Or maybe back to those! Are they related to hospitals? I think so. One reason they take a year is because it can take that long to find the actual meaning. The unforced meaning. It takes time to weave facts and feelings honestly, to find the right senses and scenes, to land on the truth. It’s easy to force a metaphor. It’s easy to tie things up into a bow. It can be super hard to find an honest conclusion about What It All Means, one that honors the experience of chaos but still finds the through-line of insight.

After a few hours of waiting and tests, the doctor who would perform Fiona’s heart repair finally walked into the exam room. She immediately brought a human presence with her. She pressed her hands together in a horizontal prayer position and looked straight at Fiona. She told Fiona, in a gentle voice, that Fiona’s only job was to take a nap. Then she explained to my husband and me how she would close the hole without surgery. She answered every question we had. She liked to look at the floor or the wall when she answered, but she was willing (and seemed to try very hard) to occasionally make eye contact. She murmured to herself the questions we were asking while we were asking them, and then answered in a calm, clear, dare I say loving way? She often started with, “Good question….” I don’t know how to say how much I loved this doctor. Then, towards the end, she drew from her white-coat-pocket the device she would use to close the hole in Fiona’s heart. It was made of polymer and titanium wire. It looked like an ivory flower, its petals arranged in a delicate circle.

What does that mean?

It means designers of medical salvation tools have an eye for beauty?

It means Nature’s design has an eye for salvation?

What does it mean that the radio played “Hole-Hearted” that day we learned of Fiona’s “moderately sized heart-hole”?

Months later, with Fiona’s heart successfully repaired—with the hole now filled by a delicate, thousand-dollar flower—I think about that drive home. And I think about what I know of the Great Divine. The Ultimate Reality. The Source we call God. And I think that the Source might have just been trying to make me laugh. Because how is this not funny:

But who knows. Sometimes you learn the hole is still open. Sometimes the truth keeps coming, keeps deepening, even years after your years-long search.

Tidbits & Things:

Readers! Holy Bananas! Just as I was finishing up this post for you, I learned that I’m the recipient of a 2024 New Jersey Artist’s Fellowship! The piece I submitted to the council? “The Heart Wing.” I celebrated by buying myself a box of pens, and scheduling a lunch date with my pal (and fellow fellowship recipient),

.I love Tricia Hersey’s nap ministry! And I so appreciate this post about the need for more silence in a world clamoring to make more content. (That’s why I have *zero* publication schedule or content calendar for The Slow Take. My approach is to never pop into your inbox until I actually have something to say.)

I have so much I need to read lately for work, but I’ve been cheating on all of it with Kiese Laymon’s How to Slowly Kill Yourselves and Others in America (Revised Edition.) Here’s a quote from Laymon:

All my English teachers talked about the importance of finding “your voice.”… What my English teachers didn’t say was that literary voices aren’t discovered fully formed. They aren’t natural or organic. Literary voices are built and shaped—and not just by words, punctuation, and sentences, but by the author’s intended audience and a composition’s form."

How about you? Reading anything good lately?

I loved the Beatitudes piece, and I love The Heart Wing. Encouraging that there is someone else out there whose work percolates for years.