Walking the Wrong Way Through Mary Cassatt

On caregiving as a not-so-sentimental act

Hello, reader! Welcome to The Slow Take, my very occasional newsletter about the strangeness and beauty of being human. I’m Heather Lanier, author of the memoir, Raising a Rare Girl, and the poetry collection, Psalms of Unknowing. I’m glad you’re here.

I had an 11-year-old in tow, so I was walking the wrong way through the Mary Cassatt exhibit. Or maybe I would have been walking the wrong way regardless. The well-lit walls featured lots of plump white babies. There many folds of gowns—sometimes the mother’s, sometimes the baby’s. The gowns were in pastel colors, created with literal pastels.

I mean, the art was heavy on early mothering. Women nursing babies, bathing babies, maybe burping and definitely snuggling babies. Did I mention the folds of pastel fabric? What about all the flesh, the pinkish-beige, doughy folds of baby legs. It was frilly and soft and sweet. One woman even had ginormous puffed sleeves. I was not super interested. Not artistically, at least.

But my eleven-year-old girl was in tow, so I rallied my intrigue. Mary Cassatt! I said. Famous American artist! Born in PA! Trail-blazing woman! Go Mary Cassatt!

And then—because we had been moving backwards by accident through Mary Cassatt—I read the description that contextualized all these babies. Childcare, read the room’s subtitle. Here was the literal writing on the wall:

“By 1900 Cassatt was widely recognized for her paintings of women and children. Two misconceptions have persistently accompanied these images: that they always depict mothers with their offspring, and that they do so in a sentimental manner…. Across these scenes, Cassatt consistently centered the labor involved in childcare, foregrounding the reddened work-worn hands of the models who bathe, dress, cajole, breastfeed, cuddle, and educate young children. By highlighting Cassatt’s attention to this work, we can see how she subtly staged childcare as active and laborious.”

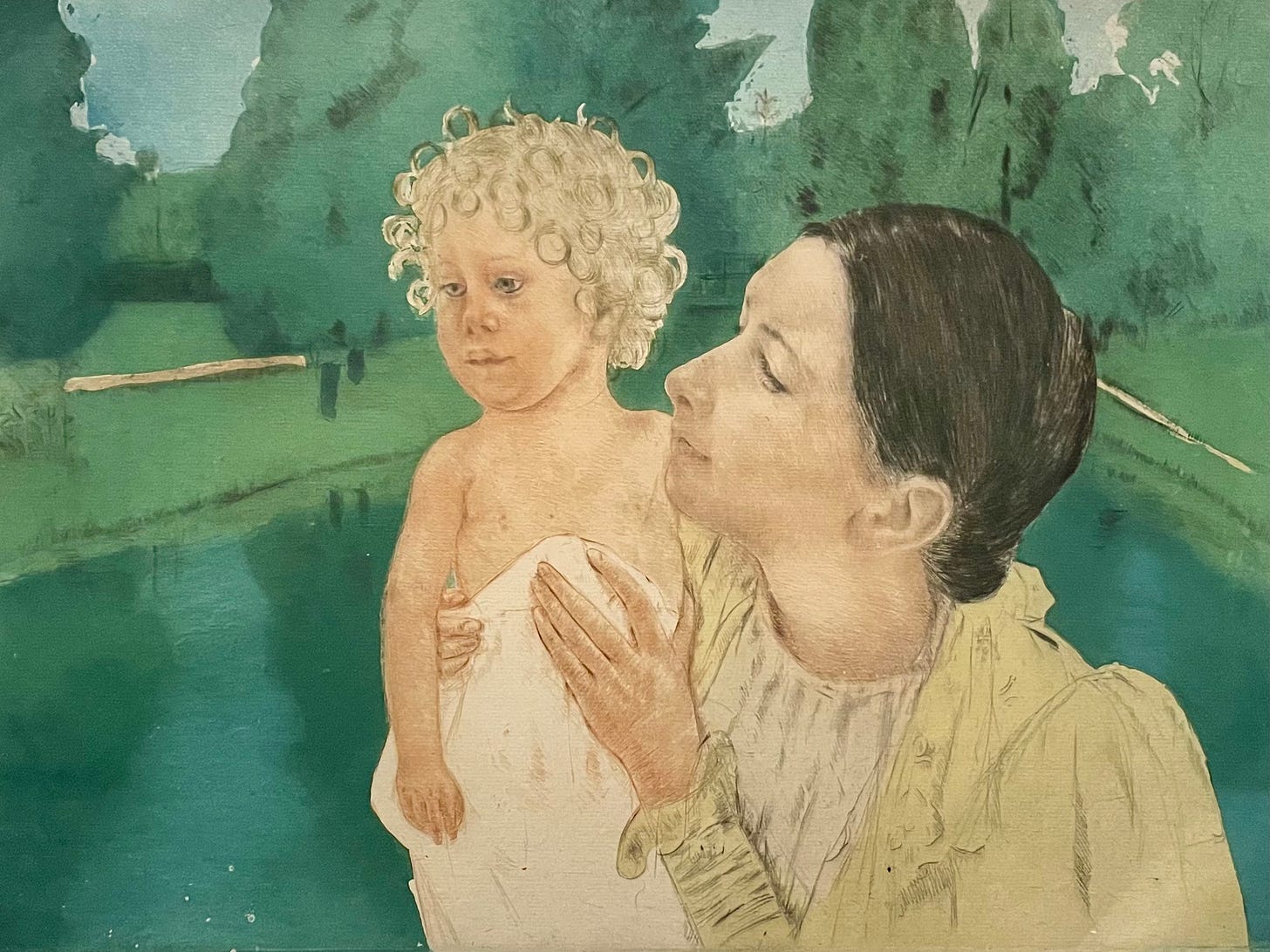

I looked more closely at the images. Sure, the feathery effects of impressionism leave a certain, well, impression that rubs against my modernist aesthetic. But. There’s also this:

The woman’s face. The disengagement in her eyes, even as her hands attempt to connect with the baby’s feet. She might not even be the mother. She might be the wet-nurse.

I’ve been there, Nursing Woman. I’ve been in the numbing mundanity, the again-and-again-ness of keeping small people alive. One might say, of this woman, Her heart isn’t in it. But any caregiver knows: Her heart might very well be in it. It’s her mind that’s elsewhere. Craving something essential. A New Yorker article, maybe. A long conversation with another grown-up.

Cherish every moment, elder ladies would say when I passed them with a baby strapped to my chest. They probably still say this. (Dear God, let none of us ever become the elder ladies who say this to young mothers.)

Back when my babies were small, I could not cherish every moment. Who can? I would need to be an enlightened monk to do such a thing. And I’m not sure even enlightened monks, as mothers, could cherish every moment.

Maybe Cassatt comes off as sentimental because there is still so much fluff in the portraits. So much stereotypical beauty. Flushed cheeks. Blond curls. Where are the fresh depictions? The counter-narratives? Caring for my first baby required drop-feeding and a hospital-grade breast-pump. It required carrying my baby’s worryingly light body to swallow studies and kidney ultrasounds. Where, Mary, are the tears? The seizures? The babies so skinny their legs could never be mistaken for dough?

Just when I started envisioning a Mary Cassatt portrait of Down syndrome, I walked past this painting and thought, maybe….

It was admittedly a stretch. But I recalled the angel in “The Adoration of the Christ Child.” Scholars say the figure just left of Mary is likely an early depiction of someone with Down Syndrome.

Still, when I combine “Cassatt” with “Down Syndrome,” Google turns up no results.

Last week, Reuters reported on the earliest known evidence of Down syndrome: the fossilized inner ear of a 6-year-old Neanderthal girl. (Thanks to my friend, Suzanne, for sharing this with me!) She lived some 200,000 years ago. The fossil revealed that she had significant disabilities, including deafness, vertigo, and “an inability to maintain balance.” Paleoanthropologists say “it is highly unlikely that the mother alone could have provided all the necessary care while also attending to her own needs…. [T]he group must have continuously assisted the mother….”

The group. We’ve needed it since the beginning. Since before the beginning. Maybe Cassatt seems sentimental to me because the portraits are always of one caregiver and one baby.

Still, I appreciate her message that caregiving is labor. Sometimes un-fun labor, mostly closed-door labor, always emotionally complex labor. It can be rewarding. It can be drudgery. I’m sorry, Mary, that I mistook your artistic display of this truth with Hallmark fluff. At least your paintings let us peak behind the domestic door.

As I write this, it’s summer. In order for me to get these words down, my kids are both sitting in front of screens. I would not trade my role as a mother for anything. And yet, I learned early on that it cannot be my only role. I loved this Romper piece by

, resisting the popular advice that mothers should just put down their phones and be present with their kids.“I want to be the mother who is present for her kids…. But I also want to stay there, reading the Ada Limón poem, my mind in the space it used to go without telling anyone where it was going or when it would be back. What if my phone is not the distraction? What if it is my child who is distracting me from being present to other worlds? To myself?”

It turns out, caregivers of the late nineteenth century were probably also feeling distracted. They were probably also in need of other stimulation, even as they stimulated the feet of the babies in their care. If this nursing mother were in the twenty-first century, she would have surely been staring at her phone.

How easily motherhood images can appear sentimental to us (to me!), even when their complexity is planted in plain sight.

There is tenderness. There is love. There is also boredom.

There is bowing to the altar of need. There are also the costs. Raw nipples, for one. Big thoughts lost to sleeplessness, another.

And there is breaking at that altar, needing others to come help.

The wrong way through Mary Cassatt is seeing caregiving as purely sentimental. As only sweetness and no struggle. As only cooing and never crushing.

The wrong way through Mary Cassatt is what I’ve spent plenty of poems and essays coaxing readers and thinkers and parents and non-parents away from doing.

And yet, today, I walked the wrong way through Mary Cassatt. I’m glad the literal writing on the wall reminded me otherwise.

And I’m glad our twenty-first century portraits of caregiving are even more complex than Cassatt’s.

How about you? What’s a portrait of caregiving that you love?

Post-Script:

If any of the above interests you, I cannot recommend this book enough: The Mother Artist: Portraits of Ambition, Limitation, and Creativity, by Catherine Ricketts. It is so good and beautiful and insightful and compelling. I had the chance to read an advanced copy. I was delighted to find it at the gift shop in the Philadelphia Museum of Art, alongside books on Cassatt. I grabbed a few copies for friends.

Last fall, I wrote a piece for Zibby Magazine about my own struggles to combine motherhood and art-making. You can read it here.

I absolutely loved this piece, Heather. & I'm honored to have my essay in this conversation. yes to all of this, and now I want to consider this prompt about a portrait of caregiving I love...xo

Interesting question. At first all the art that came to mind were all male artists using women and children as objects. Klimt’s 3 Ages of Woman is always cropped with the mother and child but the actually full piece is way different. And most of the women artists I know are creating art that excludes caretaking. When I think of caregiving art I think of craft—quilting, embroidery, recipes—items that can be useful. The love accessed when away and in need of comfort.