Hello, Slow Take readers! We have some new readers here! I’m poet and essayist Heather Lanier. This is a space about the strange beauty of being human. It’s a space where we lean into the invitations that help make us feel more human. Think of it as the opposite of a boob-implant billboard or an AI-generated “thank you” note. There are only real thank you’s here. Thanks for reading!

Today’s Slow Take is a combo personal essay + book review. It’s also about motherhood. Not all Slow Takes are of the maternal bent, so if that’s not your thing, I hope you’ll stick around.

“I’m not a good mom,” I used to tell my husband. “I’m a bad mom,” I’d sometimes say. I said it when the kids were breastfeeding, and I said it when they were toddling—one solo and the other with a walker—and I said it when they were elementary-age. I said it at every stage of childhood. “I’m a bad mom.”

My husband found my mantra confounding, even as he tried to engage with it. How could I call myself a bad mom? he wondered. I took the kids to library story hour. I threw them budget birthday parties in our backyard. For God’s sake, I even managed to give our nonverbal daughter expressive speech! The last one usually won me over. He was right: I persisted in getting our rare kid a talker and teaching her how to use it so she could actually tell the world her needs and wants. (I write about that journey in my old blog, Star in Her Eye, here and here.)

But no list of mothering tasks or achievements ever fully swayed me, and I had a hard time figuring out why, until the day that I named what I thought made a good mom.

A good mom was someone who did all those things, and enjoyed it.

It was not enough to do all the things a good mom did. I had to like it.

And much about mothering small people, I did not like.

Ergo, I was not a good mom.

This was my logic. Naming it was helpful.

I saw the pickle that my beliefs had put me in. I couldn’t control my feelings. So I could never be, by my definition, “a good mother.”

Strangely, this was a relief.

I saw the belief for what it was: an impossible yardstick. I’d never measure up. And my kids needed a mom. So I’d be the imperfect one. The “not-good” one. The one who did all the things but didn’t like a lot of them.

Where did this belief even come from? I didn’t know. It just seemed present in me, like the genetics that made my hair auburn or my eyes brown.

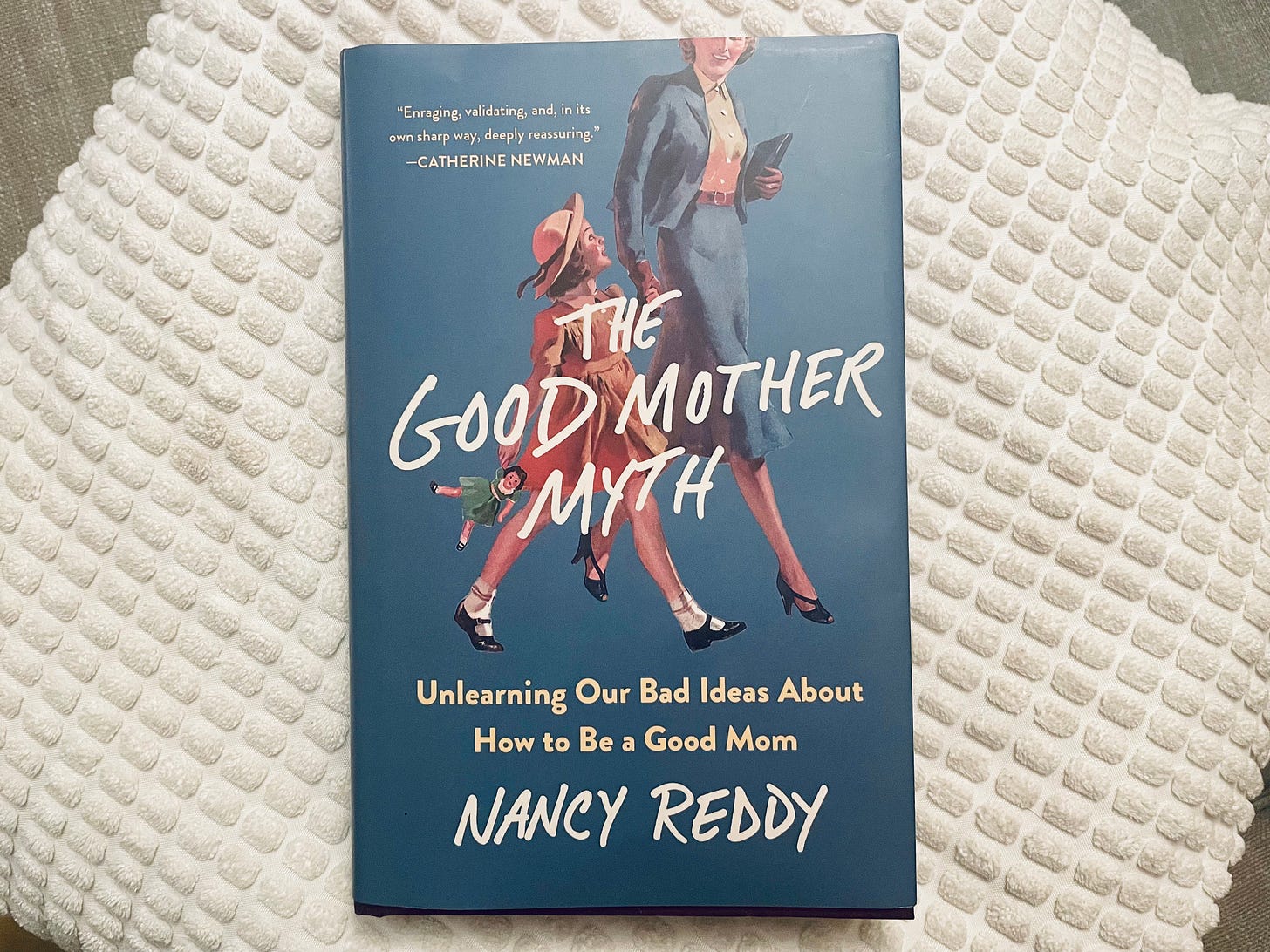

Enter

’s recently-released The Good Mother Myth! Reddy’s book investigates the bad science behind our problematic beliefs about what makes a “good mom.” She examines influential researchers of the 20th century who argued that a good mother was constantly available and attentive to her children. Twenty-four/seven. Otherwise, they could raise criminals or emotionally deficient kids.Turns out, the researchers who told women this were mostly men who spent very little time with their own kids. Turns out, the research they used to determine this view was deeply flawed and often predetermined. They knew what they wanted to prove before they did their research. Meanwhile, some of their wives wrote them letters from afar, telling them how lonely they were, how hard it was to raise their kids alone.

I’m making generalizations, and you should read Nancy’s book. But I want to dwell on one researcher, Mary Ainsworth, who was monumental in shaping the parenting paradigm most popular when I raised little kids: attachment-style parenting. She claimed that not only did women have to be fully and perpetually present to their infants; they had to like it.

Here’s Reddy: “According to Ainsworth, even mothers who gave their infants the constant care they believed they needed but didn’t like it, didn’t feel the right way about it, could still produce insecurely attached infants. … For Ainsworth, it wasn’t enough for a mother to be technically proficient. She had to feel the right way as she cared for her child.”

And there it was: the roots of my belief that a good mom felt good about being constantly available and doing all the things. Reading about the origins of this view was like a gardening experience I had last summer. A vine was choking some of the flower bushes, so I pulled at the vine, and a foot of its rope released from the soil. I pulled some more, and another foot or two released, until I found the root of the plant several meters away. There: the tenacious origins. A gnarl of knotted wood. We had to dig it up.

I wasn’t fully ignorant to these origins. I’d always noticed policing a mother’s feelings begins as soon as she conceives. I write a little about this in my memoir, Raising a Rare Girl. Pop-science headlines tell pregnant women to “think happy thoughts: Studies show your baby can feel your mood.”

But actually hearing my “good mother myth” in a flawed researcher’s report was a revelation. Reddy sums up Ainsworth’s claims this way: “Even if you’re physically there every moment, if you’re not 100 percent present, if you think of anything else or want anything else besides your baby, you’re doing just as much harm as if you’ve abandoned your child entirely.”

Ainsworth’s ideas carried into the 21st century. When I got home from birthing my first daughter, torn and still bleeding, I sat on the couch and tried to nurse her. Beside me was a 700+ page book called The Baby Book, in which the attachment parenting experts suggest that, as Reddy says, “Simply thinking of things beyond your child puts the bond at risk.”

No wonder I didn’t absolutely love mothering. I’m a person with thoughts. A writer who wants to work through ideas. I inherited the idea that, in order to be a “good mom,” I had to feel a certain way about the role AND that role had to consume me.

It was a relief, reading about these theories and seeing them for what they are: pseudo-science that puts undue pressure on a solo woman when what she really needs is community support. (Ainsworth conducted studies in Uganda, but failed to look at the village as a whole; she focused entirely on mother-daughter bonds.)

Here’s some irony: On the day that I first drafted this piece, I woke early. I read some of The Good Mother Myth in bed, and I was inspired to catch my thoughts on paper. Nobody’s awake, I thought, so I crept to my office. (A privilege, having a room of one’s own. Our house is 1400 square feet, but it still squeezes 4 bedrooms into its frame.) On the way through the living room, my now tween-age daughter called out to me. I found her on the couch. She asked if we could snuggle and watch a favorite TV show together.

Choose Your Own Adventure Time. You’re a mom with heavy guilt but also the urge to think. In order to write about the bad history of telling mothers they have to be fully present to their kids, you have to be… not fully present to your kid. Do you:

a.) Tell your kid you’ll watch the show together in a few hours, then sneak away to catch these thoughts before they flee?

b.) Let the thoughts go, hoping they’ll be there waiting for you in a day or two, when you’ll have another hour alone.

I chose a. I felt only a little guilty.

Let me know in the comments below if you resonate at all with this “good mother” myth. Or maybe you’re deconstructing a different myth. Do share!

Tidbits and Things

I have a new poetry collection out! More on that soon! It’s a chapbook (a book that’s half the length of a typical collection) and it took… wait for it… 13 years. (Hi, my newsletter is called The Slow Take.) I’ll tell the story of that collection’s long road to publishing in a future post, and I’ll offer a sneak-peak poem!

Seriously, I hope you read Nancy Reddy’s The Good Mother Myth. It’s so good. No lie, no myth.

Loved this piece, thank you so much for sharing. I wrote about this tendency to call myself a bad mother when my eldest was young and we were parenting in Northern Laos, but came at it from a slightly different angle. Love your take on it. https://lisamckaywriting.com/in-which-i-say-im-a-good-mother/

Well, here's my guilt explained! Thank you for sharing your insights.